[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

BOOKS

Trials for International Crimes in Asia

Edited by Kirsten Sellars

Cambridge University Press, 2015.

The issue of international crimes is highly topical in Asia, with still- resonant claims against the Japanese for war crimes, and deep schisms resulting from crimes in Bangladesh, Cambodia and East Timor. Over the years, the region has hosted a succession of tribunals, from Manila, Singapore and Tokyo after the Asia-Pacific War to those currently at work in Dhaka and Phnom Penh. This book draws on extensive new research and offers the first comprehensive legal appraisal of the Asian trials. As well as the famous tribunals, it also considers lesser-known examples, such as the Dutch and Soviet trials of the Japanese, the Cambodian trial of the Khmer Rouge, and the Indonesians’ trials of their own military personnel. It focuses on their approach to the elements of international crimes, and contribution to general theories of liability. In the process, the book challenges some of the prevailing orthodoxies about the development of international criminal law.

Contributors: Rehan Abeyratne, Mark Cammack, Cheah Wui Ling, Simon Chesterman, Robert Cryer, Tara H. Gutman, M. Rafiqul Islam, Neha Jain, Bing Bing Jia, Nina H.B. Jørgensen, Osawa Takeshi, Valentyna Polunina, Abdur Razzaq, Lisette Schouten and Kirsten Sellars.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

‘Crimes against Peace’ and International Law

Cambridge Studies in International and Comparative Law, Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Now out in paperback

Kirsten Sellars’ latest book, ‘Crimes against Peace’ and International Law, has just been released in paperback. Published by Cambridge University Press as part of its Cambridge Studies in International and Comparative Law series, it traces the idea of criminalising aggression — encapsulated by the ‘crimes against peace’ charge — from its origins after the First World War, through its high-water mark at the post-war tribunals at Nuremberg and Tokyo, to its abandonment during the Cold War. Today, a similar charge, the ‘crime of aggression’, is being mooted at the International Criminal Court, giving new impetus to old debates about aggression.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

‘Crimes against Peace’ and International Law

Cambridge Studies in International and Comparative Law, Cambridge University Press, 2013.

In 1946, the judges at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg declared ‘crimes against peace’ – the planning, initiation or waging of aggressive wars – to be ‘the supreme international crime’. At the time, the prosecuting powers heralded the charge as being a legal milestone, but it later proved to be an anomaly arising from the unique circumstances of the post-war period. This study traces the idea of criminalising aggression, from its origins after the First World War, through its high-water mark at the post-war tribunals at Nuremberg and Tokyo, to its abandonment during the Cold War. Today, a similar charge – the ‘crime of aggression’ – is being mooted at the International Criminal Court, so the ideas and debates that shaped the original charge of ‘crimes against peace’ assume new significance and offer valuable insights to lawyers, policy-makers and scholars engaged in international law and international relations.

Reviews

‘[This] book is more than a history of aggression; the product of comprehensive and in-depth archival research from an enviable range of sources, it is also an excellent general history of the development of international criminal law itself. There are many good books on the road to international criminal law, but if you were to read just one, I would recommend this. Its lucid pungent analysis makes it a pleasure to read.’ — Neil Boister, Edinburgh Law Review, January 2014

‘Sellars does an excellent job of highlighting the various controversies and personality clashes that almost scuttled these early, and flawed, experiments in international criminal justice. She succeeds in synthesizing a narrative in the form of a dialectic, in which the pertinent questions of international law that were raised and argued ad nauseam by the prosecution and defence, are placed in the context of great power politics, with the Allies emerging victorious from the Second World War.’ — Victor Kattan, Journal of International Criminal Justice, November 2013

‘Kirsten Sellars concentrates… on the formative period in the development of the idea of ‘crimes against peace’ in the years after the Great War through to the Nuremberg and Tokyo prosecutions that followed the Second World War. And with this focus, Sellars does a masterful job. Drawing heavily on period documents, many of them unpublished at the time, she provides a highly readable account of the fits and starts that accompanied the emergence of the notion that individuals may be prosecuted for a war of aggression.’ — John B. Quigley, International Affairs, September 2013

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

The Rise and Rise of Human Rights

Sutton Publications, 2002.

The Rise and Rise of Human Rights investigates the legal and political history of the human rights doctrine from the Second World War to recent conflicts in the Balkans and the Middle East. Using archival material, some of it previously unpublished, it examines the Cold War rivalry that overshadowed negotiations over the UN’s Universal Declaration and the human rights covenants; and analyses the factors that shaped the Nuremberg and Tokyo war crimes tribunals. It chronicles the debates about the European Convention in the fifties, the disagreements over President Carter’s human rights policy in the seventies, the issues arising from Reagan’s policies in Central America in the eighties, and, finally, assesses the significance of the recent campaigns against slavery and religious discrimination during the post-Cold War era.

Reviews

Selected as one of the books of the year, New Statesman, 2002

‘It is the eradication of evil and cruelty in society that was the engine room of the human rights revolution, no better chronicled than in The Rise and Rise of Human Rights’ — John Cooper QC, The Times (London)

‘This book is essentially a polemic, although a well-researched one, on the gap between appearance and reality with respect for the campaign for human rights’ — Stephen A. Garrett, International Affairs (London)

‘Kirsten Sellars’ Rise and Rise of Human Rights… challenges triumphalist multilateralist narratives about the abatement of traditional conceptions of sovereignty even as it highlights the way human rights ideas have come to the fore – and exerted influence – at moments when other ideals were exhausted or in abeyance’ — Elizabeth Borgwardt, Harvard Law School Legal History Colloquium

‘Sellars has a sharp eye for colourful detail, and tells a good story’ — Noel Malcolm, Sunday Telegraph (London)

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

In-gwon Geu Wiseon-eui Yeoksa

(The Rise and Rise of Human Rights)

Translator: Oh Seung-hoon, Eunhaengnamu, 2003.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

ARTICLES

Rocking the Boat: The Paracels, the Spratlys, and the South China Sea Arbitration

Columbia Journal of Asian Law 30 (2017), 221-262.

On July 12, 2016, an Arbitral Tribunal constituted under Annex VII to the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea found overwhelmingly in favor of the Philippines in its dispute with the People’s Republic of China over maritime zones and other issues in the South China Sea. This piece appraises the decision in light of the events leading up to the current controversy.

To investigate the source of the conflict, one does not have to go back very far. In January 1974, during the final stages of the Vietnam War, China ejected South Vietnam from the Paracel Islands—a group of tiny maritime features in the South China Sea claimed by both nations. After a classic “weekend war,” China tried to dampen down the affair by swiftly releasing the prisoners and refusing to be drawn into an international debate.

Within days, though, there was more activity, when South Vietnam dispatched forces to occupy five features in the Spratly Islands, a larger group further to the south of the South China Sea. During this period, South Vietnam, the Philippines, and Taiwan engaged in the fortification of their respective features—bolstering garrisons, installing military hardware, building runways, and shooting at interlopers. The militarization of the Spratlys had begun; and well before China, the focus of the current arbitration, established a physical presence on the reefs in the vicinity.

This piece examines the unfolding of the Paracels and Spratlys disputes through the lens of the United States’ diplomatic correspondence between the State Department and its missions in Asia. When the controversy ignited in 1974, the U.S. was still trying to disentangle itself from Vietnam, and had no intention of being inveigled by its Asian allies into commitments in the South China Sea. Consequently, it struck a determinedly neutral stance, stating that it took no position; a stance to which it formally adhered until 2016. But declared disinterest did not mean lack of interest, and behind the scenes, Washington played an active though little known role in trying to contain the conflict, by discouraging Saigon from pressing its Paracels claims in the Security Council, and trying to deter American oil companies from exploring Reed Bank.

This diplomatic correspondence, which the Arbitral Tribunal does not appear to have examined, casts a strong light on the interests and legal positions of the players in the South China Sea—interests which continue to govern the actions of China, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam today. When chronicling the initial phases of the current disputes, American officials not only set out the parties’ legal justifications for their actions, but also provided assessments of the merits of some of these positions. In the process, they also offered early insights into a central jurisdictional question addressed by the Tribunal: whether the Spratlys features should be defined as “islands” or “rocks” under Article 121 of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea—the matter on which we shall conclude.

Image: Wikipedia Commons

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Meanings of Treason in a Colonial Context

Leiden Journal of International Law 30 (2017), 825-845.

In 1945-46, the British colonial authorities convened a series of trials of members of the Indian National Army, a force allied with Japan. At the first, three officers were charged with ‘waging war against the King’ — or treason — set out in Section 121 of the Indian Penal Code.

If it appeared to be a straightforward treason case, the chief defence counsel, Bhulabhai Desai, soon turned it on its head, by questioning the very premise of the ‘waging war’ charge. The essence of his argument was that during a war of liberation, the justice of the challenger eclipsed the security of the challenged. He called on international law, stating that the court had no jurisdiction over belligerent states, and that the accused had no case to answer. And he used Hobbesian arguments to explain how the allegiance so peremptorily commanded by the Raj, and summarily so punished if abandoned, could be — and was — legitimately renounced.

Desai’s speech had a profound impact, and one jurist, Radhabinod Pal, would soon take his arguments to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, established to deal with ‘crimes against peace’ — treason against the society of states. Pal, like Desai, took colonialism as his starting point. He thought the Allies’ motive for

creating the ‘crimes against peace’ charge was highly suspect, because it potentially criminalised the anti-colonial struggle. Colonies, he wrote, should not be compelled to submit to eternal domination ‘only in the name of peace’. This, of course, was precisely Desai’s point.

Image: flickr

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Delegitimising Aggression: First Steps and False Starts after the First World War

Journal of International Criminal Justice (10th anniversary issue), 10 (2012), 7-40.

The interwar years marked the movement in international law towards the prohibition of aggressive war. Yet a notable feature of the 1920s and 1930s, despite suggestions to the contrary at the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals, was the absence of legal milestones marking the advance towards the criminalization of aggression. Lloyd George’s proposal to arraign the ex-Kaiser for starting the First World War came to nothing. Resolutions mentioning the ‘international crime’ of aggression, such as the draft Treaty for Mutual Assistance and the Geneva Protocol, were never ratified. And the Kellogg-Briand Pact, while renouncing war ‘as an instrument of national policy’, made no mention at all of aggression, much less individual responsibility for it. Not until the closing stages of the Second World War, with defeat of the Axis powers within sight, did politicians and jurists reconsider the problem of how to deal with enemy leaders, and contemplate the role that a charge of aggression might play in this process.

Image: npg.org.uk

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

William Patrick and ‘Crimes against Peace’ at the Tokyo Tribunal, 1946-48

Edinburgh Law Review 15 (2011) 166-196.

After the Second World War, the victorious allies convened the International Military Tribunal for the Far East to punish Japan’s leaders for crimes against peace and other war-related crimes. The crimes against peace charge had proved controversial at the Nuremberg Tribunal, and the sponsoring powers made considerable efforts to ensure that the Tokyo judgment reinforced the Nuremberg determination on it, thereby investing it with greater legal credibility. The scope and significance of these efforts has been largely unacknowledged, as has the central role in them of the British member of the court, William Patrick, a Senator of Scotland’s College of Justice.

Image: www.winstonchurchill.org

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Imperfect Justice at Nuremberg and Tokyo

European Journal of International Law 21 (2010) 1085-1102.

When the international criminal tribunals were convened in Nuremberg and Tokyo in the mid-1940s, the response from lawyers was mixed. Some believed that the Second World War was an exceptional event requiring special legal remedies, and commended the tribunals for advancing international law. Others condemned them for their legal shortcomings and maintained that some of the charges were retroactive and selectively applied. Since then, successive generations of commentators have interpreted the tribunals in their own ways, shaped by the conflicts and political concerns of their own times. The past two decades have seen the establishment of new international courts, and an accompanying revival of interest in their predecessors at Nuremberg and Tokyo. Recent commentaries have analysed the founding documents, the choice of defendants, the handling of the charges, the conduct of the cases – and also the legal and political legacies of the tribunals. They demonstrate that long-standing disagreements over antecedents, aims and outcomes have still not been settled, and that the problems inherent in some of the original charges have still not been solved, despite the appearance of similar charges within the remit of the International Criminal Court today.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

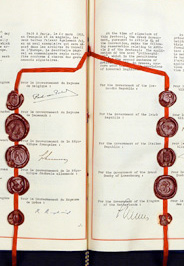

Human Rights and the Colonies

Round Table 93 (2004) 709-724.

When anti-colonialism was at its peak in the 1950s and 1960s, many colonial powers stonewalled, but Britain accommodated. It extended the European Convention on Human Rights to most of its colonies, and helped to nurture the fledgling British human rights movement. Its motive was self-interest: by being seen to invoke human rights, it hoped to neutralize attacks on its colonial practices emanating from the United Nations, and to curry favour with critics at home. This seemed to be a low-risk strategy, yet it was to prove otherwise. In the 1950s the European Commission for Human Rights investigated a complaint that Britain was breaching the European Convention in Cyprus. And in the 1960s Whitehall was forced to review its relationship with human rights NGOs after headline-making revelations about its covert support for Amnesty International. As it learnt to its cost, human rights advocacy could be a double-edged sword.

Image: multimedia.echr.coe.int

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

CHAPTERS

Definitions of Aggression as Harbingers of International Change

in Leila Sadat (ed.), Seeking Accountability for the Unlawful Use of Force (Cambridge University Press, 2018), 122-153.

Debates about definitions of aggression are responses to deadlock and harbingers of change. Each, in its own way and in its own time, has heralded a transition from an old to a new set of legal and institutional arrangements. The definitions of the early 1930s, responding to the League’s failings, signaled the legal shift away from belligerency and neutrality and towards legitimate and illegitimate wars. The Cold War definitions of the early 1950s, responding to Security Council stalemate, announced the UN’s transition from collective security organization to conflict mediator. The General Assembly’s definition of 1974, negotiated during the era of détente, might have heralded new alignments between the powerful states had the new Cold War not intervened. And the definition in the 2010 Kampala Amendment, anticipating moves from a unipolar to a multipolar world, proposes dual sources of authority — the Security Council and International Criminal Court — in the handling of aggression.

Although debates about definitions herald change, they have also given rise to remarkably durable patterns of state behavior: patterns still being repeated to this day. The most consistent advocates of automatic determinants of aggression have been states vulnerable to attack or excluded from either the League or Security Council. These ‘excluded’ states have not only looked to definitions for legal protection against the vicissitudes of international life, but have also tried to use them to break the powerful states’ monopoly over the determination of aggression. By contrast, the most powerful states, such as the ‘included’ members of the League or Security Council, have been consistently inconsistent in their approach to definitions of aggression, and oscillate according to the force-fields exerted by other powerful states. They do not want to surrender their own control over decisions about aggression, but for limited and expedient ends — say, to exert pressure on another ‘included’ state — are sometimes prepared to initiate or support definitions. With these recurring motifs in mind, we will examine three pivotal moments in the evolution of definitions of aggression — 1933, 1950, and 1974 — and in their light,

will conclude with an assessment of the latest definition proposed at Kampala in 2010.

Image: The National Archives (UK).

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

International Crimes Tribunals, Bangladesh

in Dictionnaire Encyclopédique de la Justice Pénale International (Paris: Berger-Levrault, 2017) 968-970.

The People’s Republic of Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan, emerged out of a bloody nine-month war of secession from the Federation of Pakistan in December 1971. Shortly after Pakistan’s surrender, the provisional President, Mujibur Rahman, proposed two sets of trials: one to deal with local collaborators with the Pakistani authorities, and the other to deal with Pakistanis accused of committing major crimes during the war. The current International Crimes Tribunals, which have been hearing the cases of Bangladeshi citizens accused of involvement with international crimes during the 1971 war, are the completion of this project.

Image: Wikipedia Commons

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Treasonable Conspiracies in Paris, Moscow and Delhi: The Legal Hinterland of the Tokyo Trial

in Kirsten Sellars (ed.) Trials for International Crimes in Asia (Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 25-54.

It is widely held that the idea of transplanting ‘conspiracy’ from domestic law into international criminal law was first conceived by an American working in the US War Department in the final year of the Second World War. Yet this account is not the whole truth. It is merely a part – and an atypical part at that – of a much bigger story that had begun a full quarter of a century earlier. Discussion about internationalised modes of liability had first arisen during the closing phase of the First World War, when French lawyers had grappled with the problem of prosecuting Wilhelm II and his circle; and it developed further during the Second World War, when Soviet lawyers contemplated similar actions with respect to Hitler and his minsters. This civil law approach made more sense than the Americans’ conceptual leap from the Marino conspiracy to the Nuremberg Charter, and more accurately reflected the climate of realism that gave rise to international criminal law.

Treason trials provided a template for international tribunals, and in the process, the latter spawned new charges of international treason. Interaction between the different bodies of law created the potential for ideas to travel both ways, and this is exactly what happened at the British-run treason trial convened to try senior figures in the Indian National Army at the Red Fort in Delhi in 1945. The defence counsel, Bulabhai Desai, turned the treason charges back against the prosecution, stating: ‘What is now on trial before the Court is the right to wage war with immunity on the part of the subject race for their liberation.’ Thus, from within a treason trial emerged a legal critique of the supremacy of domestic security law. This argument strongly influenced Indian advocates and judges, one of whom, Radhabinod Pal, would take it to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, and use it to challenge the charges of conspiracy to commit ‘crimes against peace’.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

The First World War, Wilhelm II and Article 227: The Origin of the Idea of ‘Aggression’ in International Criminal Law

in Claus Kress and Stefan Barriga (eds), The Crime of Aggression – A Commentary (Cambridge University Press, 2016), 21-48.

It is well known that David Lloyd George declared his intent to try the Kaiser for starting World War I, but it is not known that British lawyers embarked on detailed behind-the-scenes plans for prosecuting him — plans now brought to light in newly uncovered archival documents.

At the end of the First World War, Lloyd George declared: ‘The Kaiser must be prosecuted. The war was a crime.’ This was a radical departure from the traditional approach to war, advancing the then-novel ideas that starting an aggressive war was a crime, and that national leader could be held criminally responsible.

After the signing of the Versailles Treaty in June 1919, the British Attorney General, Sir Gordon Hewart, quietly began laying the groundwork for Wilhelm II’s prosecution, in case the latter fell into entente hands. These plans – unheralded then and overlooked since – were set in motion in August 1919, when Hewart convened a meeting between himself, the Solicitor General, the Procurator General, and two senior barristers, Frederick Pollock and George Branson.

As it turned out, the ex-Kaiser never faced trial. Six days after the Versailles Treaty came into force, the entente powers requested that the Netherlands, where Wilhelm II had sought asylum, deliver him for trial. The Dutch refused, and Hewart pulled the plug on the British prosecution project.

Image: Wikipedia Commons

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

The Defence Approach to the ‘Crimes against Peace’ Charge at the Tokyo Tribunal

When the International Military Tribunal for the Far East opened in Tokyo on 3 May 1946 to try twenty-eight former Japanese leaders, the Allies had various compelling reasons for laying strong emphasis on ‘crimes against peace’, none of them particularly estimable: the Americans wanted to explain away the military debacle at Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Soviets wanted to excuse their treaty-breaking invasion of Manchuria in 1945, and the colonial powers wished to justify their reclamation of colonies after the war. So of the fifty-five counts in the indictment, thirty-six dealt with wars of aggression. These held the defendants collectively guilty of a conspiracy to wage aggressive wars, and individually responsible for the initiation and waging of those wars. While the remaining charges covered war crimes, murder, and, nominally, crimes against humanity, ‘the most important object’, the New Zealand prosecutor Ronald Quilliam noted, was ‘the conviction and punishment of the persons responsible for the policy of waging wars of aggression and expansion.’

The defence teams faced an uphill struggle. They had been given the task of defending leading politicians and generals who had either orchestrated or failed to prevent assaults on Manchuria, China, Southeast Asia and the Pacific. And yet, for reasons not entirely of their own making, they were not only able to marshal adequate arguments against ‘crimes against peace’ charges, but also, occasionally, to turn the tables on the prosecuting powers.

Image of Takayanagi Kenzo: Wikipedia Commons

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

The Legacy of the Tokyo Dissents

in Claus Kress and Stefan Barriga (eds), The Crime of Aggression – A Commentary (Cambridge University Press, 2016), 113-141.

It is widely held that the Nuremberg Tribunal had an enduring influence, whereas the Tokyo Tribunal did not. On the issue of aggression, however, the reverse is true.

Nuremberg’s great innovation, crimes against peace, designed to highlight the German leaders’ assault on the world order, was almost immediately dismissed as a legal anomaly. By contrast, the debates that arose at Tokyo in relation to crimes against peace – on just and unjust wars, the scope of self-defence, and old and new forms of domination – endured for another quarter of a century. Yet it was not Tokyo’s Majority Judgment, but rather the dissents from it, that prevailed. Several judges took issue with the charge, and (after the sentences were handed down)

most other jurists, including those advising the prosecuting powers, tacitly followed suit.

But while the idea of trying individuals for aggression was dying out, various ideas for preventing state aggression were brought to life, driven by states’ persistent desire for security. If the first phase of the UN – the era of collective security – had been characterised by the Security Council regulation of force and the prioritisation of

global security over justice, then the second phase of its existence – the era of superpower conflict – would be defined by the breakdown of collective security and the emergence of ‘just cause’. The weakening of the UN Charter during this second phase meant that all member states now fell back on the more traditional protections

afforded by national sovereignty. At the same time, some of the less secure and smaller members began to cast around for alternative mechanisms to safeguard themselves and their interests. This resulted in a campaign for a definition of aggression that could be used as a method of determining its occurrence if, or when, the Security Council was deadlocked.

Could a definition of aggression rise above the particularist demands of its various protagonists? In the UN, numerous resolutions addressing the question of aggression were considered in the 1960s and 1970s, with the most comprehensive of these, the ‘Definition of Aggression’, being negotiated between 1968 and 1974.

This particular debate was shaped by the period of détente, and, in contrast to earlier debates, was dominated by Western attempts to prevail over the non-aligned states rather than the Soviet Bloc. Indeed, the Definition was eventually agreed upon because the West and the Soviet Bloc were able to reach an accommodation between themselves while jointly exerting pressure on the non-aligned states to abandon cherished positions.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Trying the Kaiser: The Origins of International Criminal Law

in Morten Bergsmo, Cheah Wui Ling, and Yi Ping (eds.), Historical Origins of International Criminal Law (TOAEP, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2014), pp. 195-211.

In late 1918 the Entente powers proposed trying the just-abdicated Kaiser and his subordinates for starting the war and committing crimes during its course. Policymakers and jurists not only set out an international jurisdiction over war crimes for the first time; they also proposed new categories of crimes (the precursors to ‘crimes against peace’ and ‘crimes against humanity’). In the process, they engaged in sophisticated debates about the implications of these steps – arguments that would later be rehashed at Nuremberg. Here, we will examine these original perspectives, focusing on the work of the official advisors to the British and French governments – including John Macdonell, John Morgan, Ferdinand Larnaude and Albert Geouffre de Lapradelle – as well as three influential commentators: the French jurist, Louis Le Fur, the American lawyer, Richard Floyd Clarke, and the British official, James Headlam-Morley. Over the course of just eight weeks, from late October to early December 1918, they turned their attention to the proposed trial of Wilhelm II, and offered strikingly prescient insights into the issues that shaped – and would continue to shape – international criminal law.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Founding Nuremberg: Innovation and Orthodoxy at the 1945 London Conference

in Morten Bergsmo, Cheah Wui Ling, and Yi Ping (eds.), Historical Origins of International Criminal Law (TOAEP, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2014), pp. 541-562.

No document better conveys the roughness and expediency of the negotiations leading up to the tribunal at Nuremberg than the transcript of the four-power London Conference, held from 26 June to 2 August 1945. Their success was by no means assured: the Americans repeatedly threatened to walk out, the British fretted over German counter-charges, the French objected to crimes against peace, and the Soviets refused anything other than ad hoc charges. This was history in the making, and its making was an unedifying business.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Jimmy Carter

in David P Forsythe (ed), The Encyclopedia of Human Rights (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) 247-251.

Jimmy Carter’s election as President of the United States in 1976 heralded a new era after the ordeals of Vietnam and Watergate. His emphasis on human rights was intended to signal a return to traditional American values, although the tension between his attempt to capture the public imagination and the need to maintain a flexible foreign policy resulted inevitably in compromise. His human rights policy has nevertheless endured, and its influence can be seen in the words and actions of all his successors.

Image: www.legacyamericana.com

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

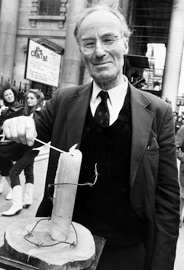

Peter Benenson

in David P Forsythe (ed), The Encyclopedia of Human Rights (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) 162-165.

Peter Benenson was a champion of ‘prisoners of conscience’ and founding member of Amnesty International. During his five years at its helm, he developed an approach to campaigning that provided a blueprint for the human rights movement. He was ambitious, innovative, and occasionally reckless, sparking controversies that would cast a shadow over the organisation he had founded.

Image: www.khalilur-rahman.com

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””][/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

BOOK REVIEWS

International Law and Organizations

(No Enchanted Palace: The End of Empire and the Ideological Origins of the United Nations by Mark Mazower), International Affairs 86 (2010) 764-765.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””][/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Human Rights and Ethics

(A New Deal for the World by Elizabeth Borgwardt), International Affairs 82 (2006) 576-577.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

EDITED WORKS

The Review, Autumn 2008

The Review, published by the Aberdeen University Alumnus Association, Vol. LXII, 1 No. 217 Autumn 2008. Featuring Alexander Fenton, Kebbocks, Kail, Brose and Breid; Cosmo Landesman, Publish and Be Depressed; Alistair Dawson, Walls of Water; Richard Turbet, ‘Things Worthy of Note’: The Common Knowledge of the Chapbook; and Hugh Pennington, The Microbe-hunters of Aberdeen.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]

[ezcol_1quarter id=”” class=”” style=””] [/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/ezcol_1quarter][ezcol_3quarter_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

The Review, Winter 2009

The Review, published by the Aberdeen University Alumnus Association, Vol. LXII, 2 No. 218 Winter 2009. Featuring Isobel Murray, Travelling Light; Forbes W. Robertson, Spade, Rake, Dibble: Gardeners’ Fraternities in Scotland; Mick Hume, The Ferguson Factor; Amanda Wrigley, Antigone and the ‘Theban Maidens’ in Aberdeen, 1919; Gwen Chessell, The Many Lives of Alexander Collie.

[/ezcol_3quarter_end]